Este artículo forma parte de la serie “Attitude”, comisariada por Hidden Architecture, donde exploramos la producción actual de arquitectos contemporáneos que, a pesar de las diferencias manifiestas de contexto físico o cultural, comparten una atención práctica hacia el valor social de la arquitectura como estructura pública.

“El verdadero constructor, el arquitecto, puede construirnos los edificios más útiles porque conoce todo lo relativo a los volúmenes. De hecho, puede crear una cajita mágica que contenga todo lo que vuestro corazón pueda desear. Escenarios y actores materializan el momento en el que la cajita mágica aparece; la cajita (…) lleva en sí cuanto es necesario para realizar milagros, levitación, manipulación, distracción, etc. El interior del cubo está vacío pero vuestro espíritu inventivo lo llenará con todo aquello que constituya vuestros sueños…a semejanza de las representaciones de la antigua Commedia dell’Arte”.

Así pues, el fenómeno de la homogeneización en la arquitectura de hoy se expresa de un modo completamente distinto de la búsqueda estética del espacio universal. Lo que está homogeneizado hoy en día es la propia sociedad, y los arquitectos luchan en vano contra ello. Cuanto más se atiene un arquitectoa expresiones características, o más bien personales, más homogéneas llegan a ser sus obras, como si fueran puntos coordenados de la geometría euclidea igualmente conectados. Éste es el momento en que la sociedad entera queda envuelta en una gigantesca película transparente.

Toyo Ito, Architecture in a simulated city

When Le Corbusier defined the spatial conception he called “boites à miracles” in volume VII of his “Oeuvres Completes”, he somehow restricted the scope of the architect to the construction of beautiful, useful, dreamlike “boxes” which unfold within them a series of perceptive events capable of making us levitate. A box of miracles, determined and deterministic, a spatial configuration fixed at the service of the spectacle, mainly visual.

Break the box, get out of it and ignore the pieces beneath our feet. To leave the box and run through the countryside, liberated at last from the homogenizing yoke of contemporary society. Thus the architectural space is conceived as a field, leaving behind the physical and phenomenological limitations of the box, as a configuration of isotropic points capable of providing the freedom that the box denied.

Parte de la producción y esfuerzos de las vanguardias, y como extensión de múltiples manifestaciones artísticas a lo largo del siglo XX, entre las cuales necesariamente se encuentra la arquitectura, han centrado sus esfuerzos en la destrucción de la caja, milagrosa o no.

Si por ahora obviamos todas aquellas aproximaciones formalistas, más evidentes, por destruir la caja, podríamos enfocar nuestra mirada en aquellos intentos por liberarse de la imposición espacial de la caja de una manera más operativa, funcional incluso si se quiere. Unos intentos que frente a la homogeneización que impone un canon determinado, muchas veces convencidamente como dogma, pretenden otorgar al usuario cierta flexibilidad en la utilización, configuración o interpretación del espacio.

Romper la caja, salir de ella e ignorar los pedazos que quedan inertes a nuestros pies. Salir de la caja y correr por el campo, liberados al fin del yugo homogeneizador de la sociedad contemporánea. Se concibe así el espacio arquitectónico como un campo, dejando atrás las limitaciones físicas y fenomenológicas de la caja, como una configuración de puntos isotrópicos capaces de proporcionar la libertad que la caja negaba.

Arquitectura como un campo de milagros.

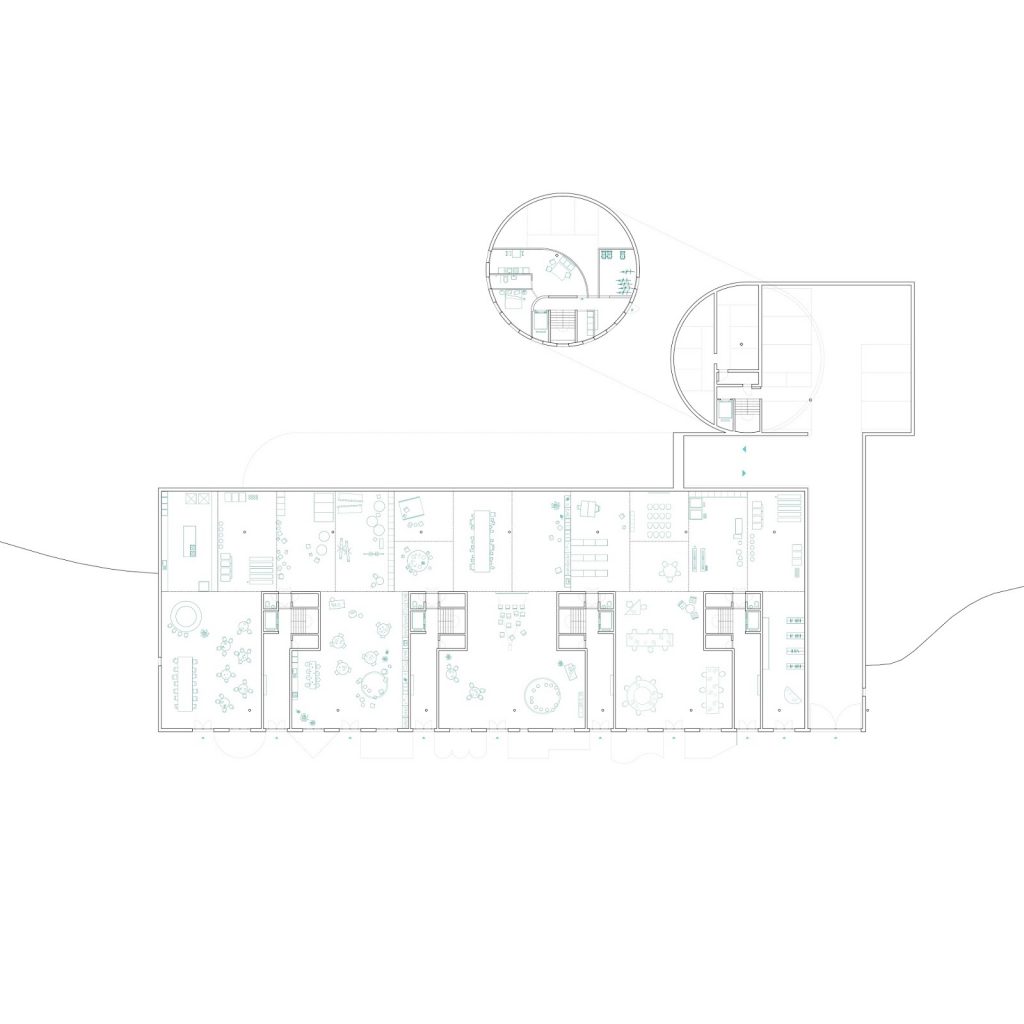

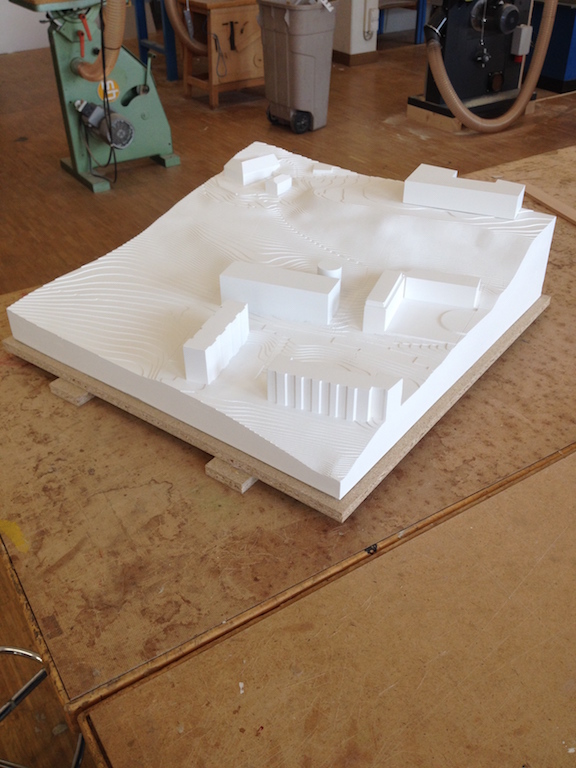

The collective housing proposal called “Champs de Miracles” by Fala Atelier is situated on a plot of northern Lausanne. With an east-west orientation, the site presents a remarkable ascending slope towards its rear area, being delimited in its more eastern side by a slope and a tree mass protecting it of the adjoining airport.

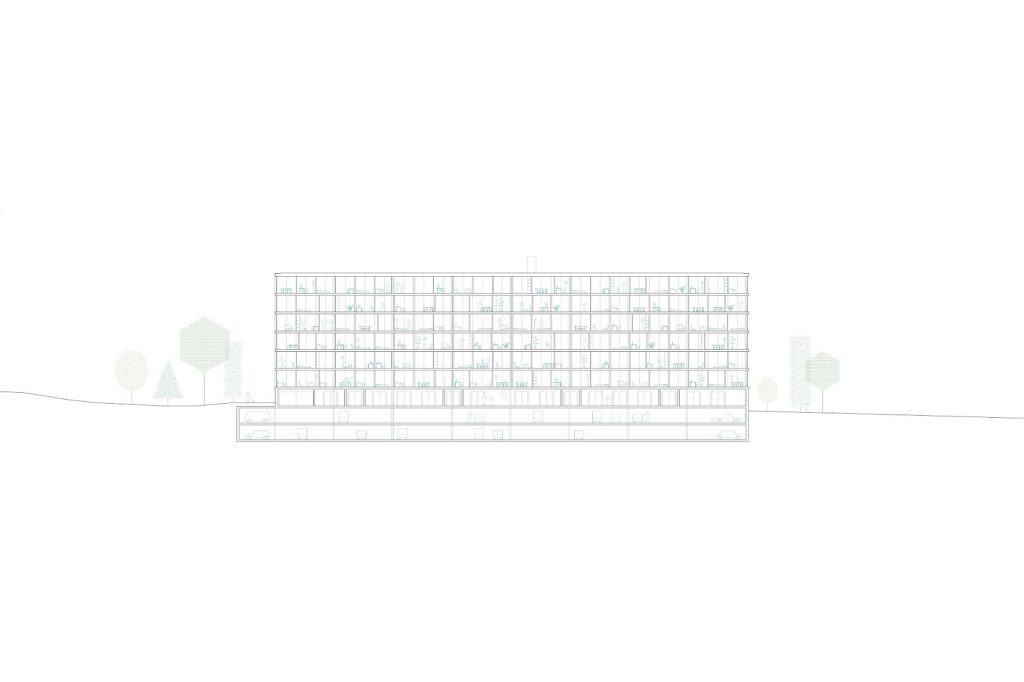

Located in a hinge between the city and countryside, the proposal by Fala Atelier aims to respond at the same time to these two situations superimposed over time and place. On one hand, it proposes a prism of clear and forceful geometry, solid in its limits. This block is aligned to the western limit of the plot, defining a markedly urban character that intends to give continuity to the fabric, already diffuse, in this area of the city.

On the other hand, the second element of the proposal is clearly separated from the first, both from a volumetric and conceptual point of view. Conceived as a cylinder, this second building is much more ambiguous in its urban definition. Its Platonic volumetry gives it a slightly monumental presence. Its independence from the linear block, and also from the urban context, define it as a sort of Palladian village, a “Rotonda” that displays in height typologies opened to a rural-like space.

La propuesta de vivienda colectiva llamada “Champs de Miracles” de Fala Atelier se sitúa en un solar al norte de la ciudad de Lausanne. Con una orientación este-oeste, el solar presenta un notable desnivel ascendente hacia el fondo, siendo delimitado en su lado más oriental por un talud y una masa arbórea que lo protegen, en parte, del aeropuerto colindante.

Situado en una charnela entre la ciudad y el campo, la propuesta de Fala Atelier pretende dar respuesta al mismo tiempo a esas dos situaciones superpuestas en tiempo y lugar. Por un lado, se propone un prisma de geometría clara y contundente, sólido en sus límites. Este bloque se alinea al límite occidental de la parcela, definiendo un carácter marcadamente urbana que pretende dar continuidad al tejido, ya algo difuso, en esta zona de la ciudad.

Por otro lado, el segundo elemento de la propuesta se separa claramente del primero, tanto desde un punto de vista volumétrico como conceptual. Concebido a modo de tambor cilíndrico, este segundo edificio se muestra mucho más ambiguo en su definición urbana. Su volumetría platónica le otorga una presencia ligeramente monumental. Su independencia respecto al bloque lineal, y así mismo del contexto urbano, lo definen como una suerte de villa palladiana, una Rotonda que despliega en altura tipologías que se abren a un espacio de carácter más rural.

Being opposed to the linear block, which holds single orientation typologies that open from a service core to the perimeter of the volume, the cylindrical block develops much less hierarchical housing, more open in terms of its functional development and closer to rural environment already guessed from this diffuse edge of the city.

Thus, these two Platonic volumes respond independently to the dichotomy imposed by its location. On the one hand, the linear block aims to give continuity to the urban fabric, it tells us about the city, while on the other, the cylindrical block already announces the end of it, a closure that gives way to a larger territory, and with which it tries to be linked, perhaps in a more conceptual than physical way.

Frente al bloque lineal, que presenta tipologías de una sola orientación que desde un núcleo de servicio se abren hacia el perímetro del volumen, el bloque cilíndrico desarrolla unas viviendas mucho menos jerarquizadas, más abiertas en cuanto a su desarrollo funcional y una relación más cercana al entorno rural que se adivina ya desde este borde difuso de la ciudad.

Así, estos dos volúmenes platónicos responden de manera independiente a la dicotomía que su ubicación les impone. Por un lado, el bloque lineal pretende dar continuidad al tejido urbano, nos habla de la ciudad, mientras que por otro, el bloque cilíndrico nos anuncia ya el fin de la misma, un cierre que da paso a un territorio más vasto, de explotación agrícola y con el que pretende vincularse, quizá de manera más conceptual que física.

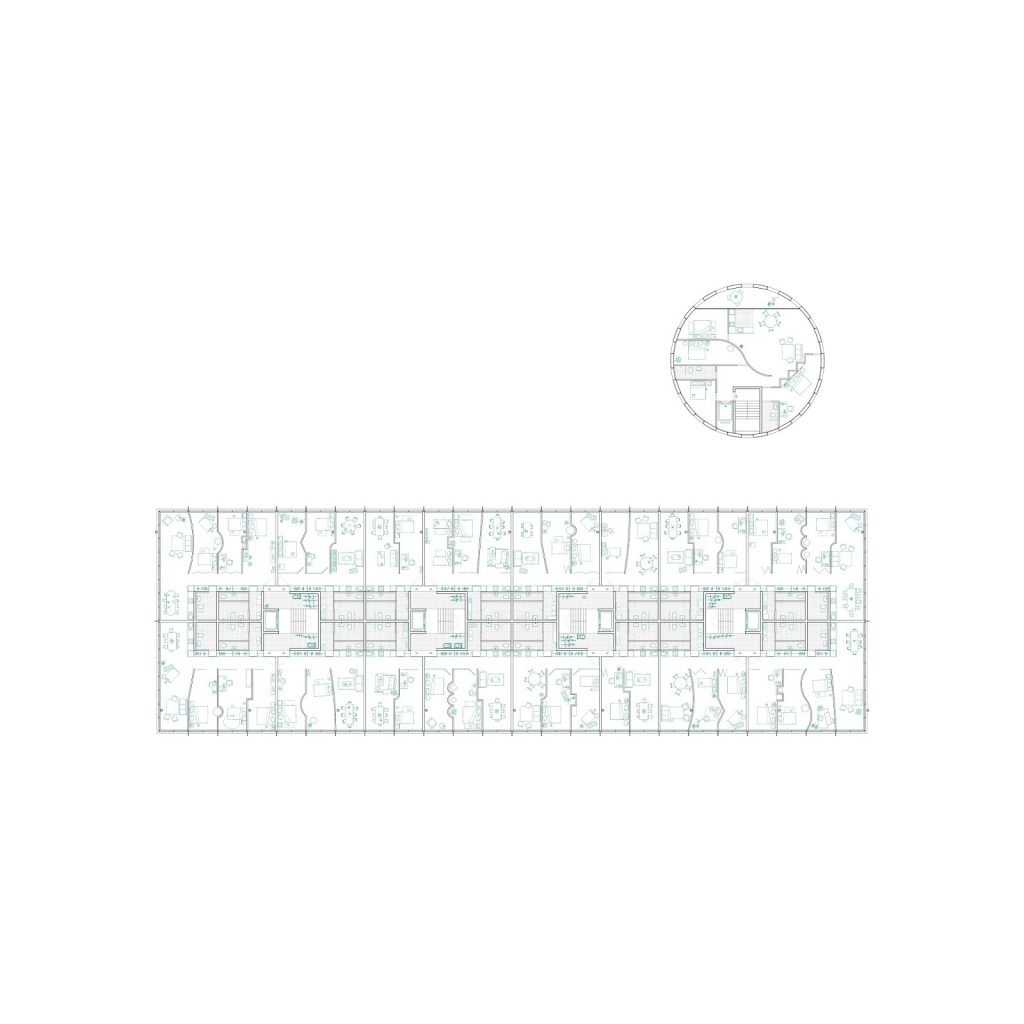

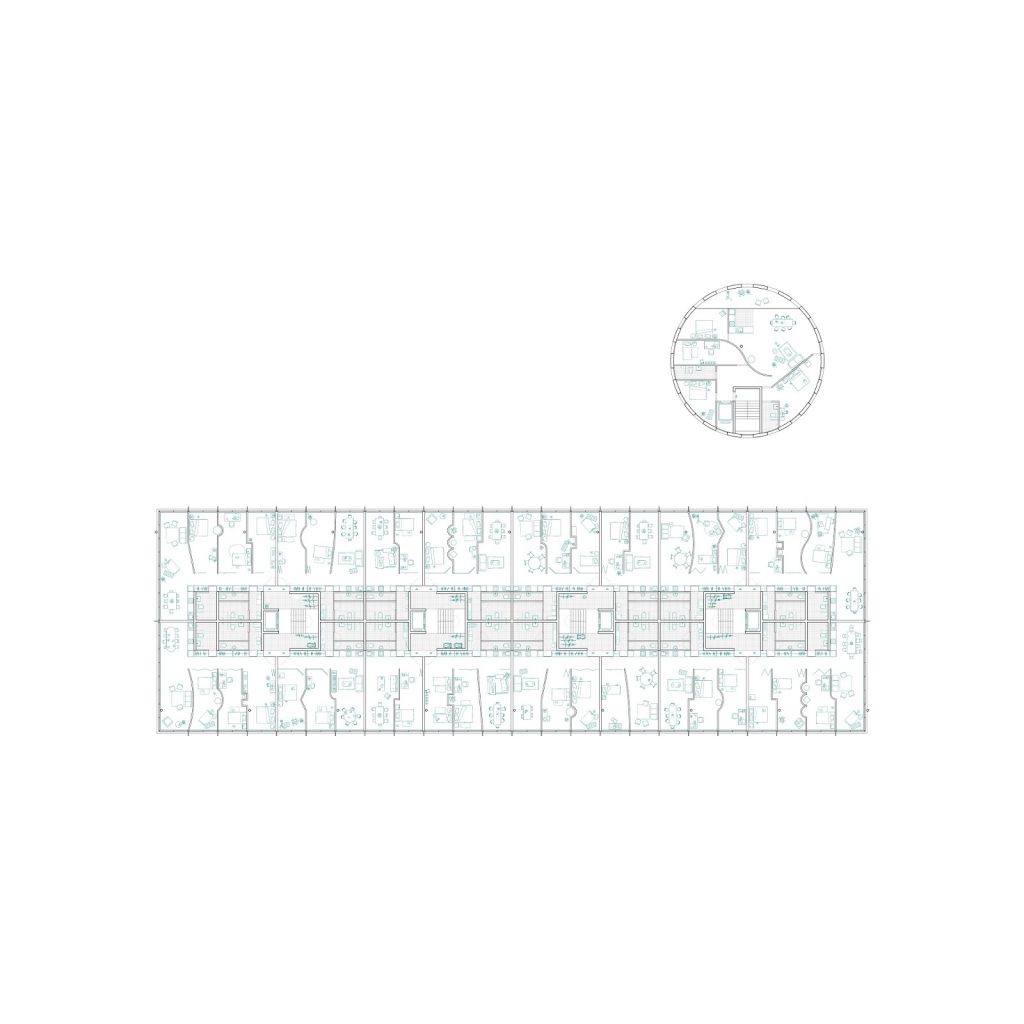

Considering the typological definition of the different housing units, it is clear that the idea of ”Support” developed by N.J. Habraken is very present in the definition of the linear block.

It presents a very clear orientation defined by its alignment to the street, an east-west axis. Thus, the different houses, with the exception of those placed in the corner, present fairly homogeneous conditions, although different orientations make some apartments comfort conditions better in summer and others during winter.

Disregarding those houses located on the corner, the rest have a single orientation, which limits in some way the possibilities of granting a more complex spaciality to domestic space. The simultaneous lighting of all rooms and the impossibility of cross-ventilation determine a rigid scheme where, a priori, the characterization of polyvalent or ambiguous rooms is more complicated.

En cuanto a la definición tipológica de las distintas unidades habitacionales, se puede apreciar nítidamente que la idea de “Soporte” desarrollada por N.J. Habraken está muy presente en la definición del bloque lineal.

Éste presenta una orientación muy clara definida por su alineación a la calle, un eje este-oeste. Así las diferentes viviendas, exceptuando las colocadas en esquina, presentan unas condiciones bastante homogéneas, aun siendo su orientación en unas, las que miran a oeste, más favorable en invierno y en las otras, a este, en verano.

Exceptuando, como se ha dicho, aquéllas viviendas situadas en esquina, el resto presentan una única orientación, lo que limita bastante las posibilidades de otorgar un funcionamiento más complejo al espacio doméstico. La iluminación simultánea de todas las estancias y la imposibilidad de ventilación cruzada determinan un esquema rígido donde, a priori, la caracterización de estancias polivalentes o de uso ambiguo es más complicada.

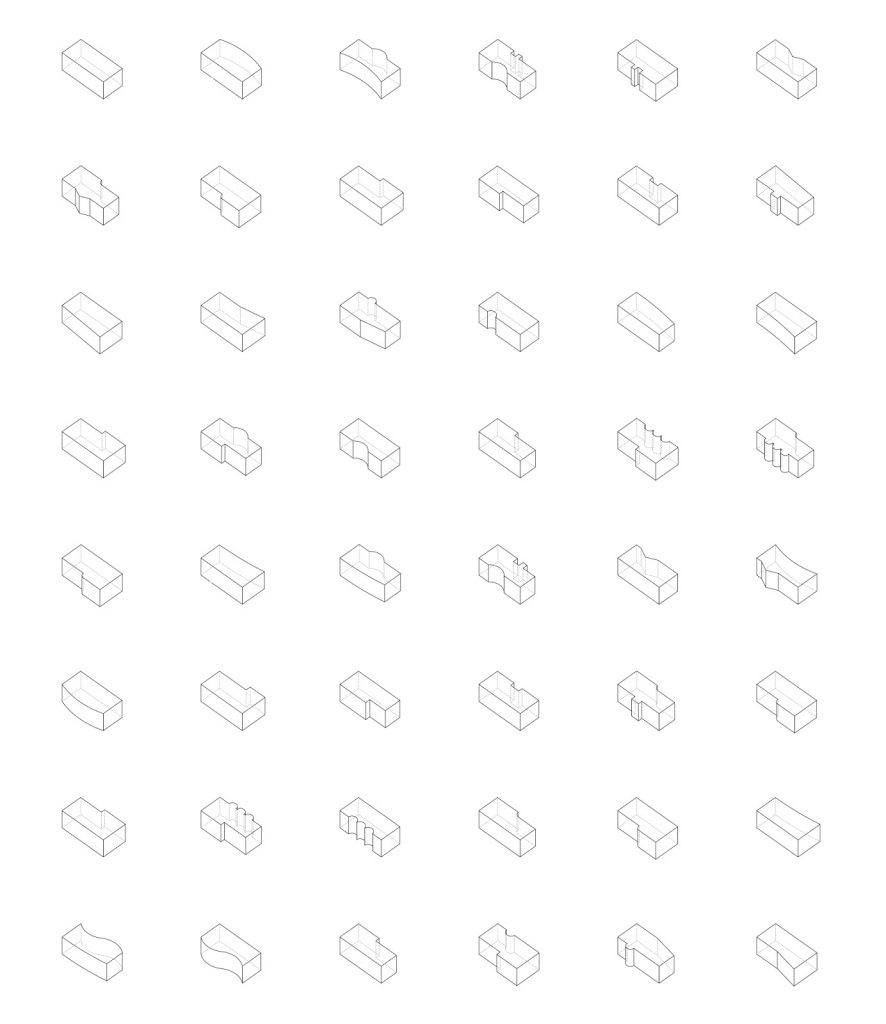

Thus, Fala Atelier bets on trying to ensure that each housing has the greatest possible flexibility in its present configuration and, above all, in the reconfiguration of the domestic space during possible and unforeseen future situations. A central core is defined, the “support” that houses vertical communications, access spaces and humid areas of the dwelling. In short, every rigid infrastructure that allows the remaining spaces to function, thus freeing the perimeter of the block from any kind of functional easement. This scheme, moved directly to a model of social housing, recalls for its clarity the one of buildings in height of greater dimensions and technical requirements. Its scheme of pragmatism allows these social housing, with very small dimensions and budgets of execution, a freedom of reconfiguration, and thus potential spatial quality, which otherwise would have been impossible. Service spaces and their environmental qualities, whether public as the core of communications or private as the toilets or kitchens, are sacrificed in some way, since they are not able to have natural lighting or ventilation, in favor of this freedom of use and reconfiguration of domestic rooms.

Así, Fala Atelier apuesta por tratar de garantizar que cada una de las viviendas disponga de la mayor flexibilidad posible en su configuración presente y, sobre todo, en la reconfiguración del espacio doméstico ante posibles e imprevistas situaciones futuras. Se define un núcleo central, el “soporte” que alberga comunicaciones verticales, espacios de acceso y zonas húmedas de la vivienda. En definitiva, toda la infraestructura rígida que permite que el resto de espacios pueda funcionar, liberando así el perímetro del bloque de cualquier tipo de servidumbre funcional. Este esquema, trasladado directamente a un modelo de vivienda social, recuerda por su claridad a la de edificios en altura de mayores dimensiones y requisitos técnicos. Su esquema en planta de gran pragmatismo permite dotar a estas viviendas sociales, de dimensiones y presupuestos de ejecución muy reducidos, de una libertad de reconfiguración, y así calidad espacial potencial, que de otra manera hubiera sido imposible. Se sacrifican de alguna manera los espacios de servicio y sus cualidades ambientales, ya sean públicos como el núcleo de comunicaciones o privados como los aseos o cocinas, puesto que no pueden disponer de iluminación ni ventilación natural, a favor de esta libertad potencial de uso y reconfiguración de las estancias domésticas.

This generosity towards future proposes the intention of allowing the inhabitants to take ownership of their domestic space and transfigure it at will, somehow allows them to satisfy their needs and give them the option, without requiring a big investment, to fulfill their potential desires. On the other hand, the absolute liberation of easements thanks to the central “support” entails a certain risk of facing this prospective development. The lack of catalysts or condensers of this future reconfiguration could cause that, within an absolute freedom, the users are not able to manage the space on its own in an optimal way and they could end up worsening the environmental conditions of it. In these same plants, it would have been interesting to have a series of alternative configurations to the model required by the requirements of the program in the contest, which illustrate in a didactic and visual way the development potential that this approach can offer.

In order to emphasize the clear division between “support” and “movable units”, the nonstructural divisions between different spaces are drawn in an arbitrary and unprejudiced way, by broken lines, curved directives, in zigzag or building niches. This representation should be understood more as a manifesto of intentions, as a theoretical approach that makes clear its true vocation through its graphic materialization: freedom of configuration.

Esta generosidad de cara al futuro plantea la intención de permitir que los habitantes puedan apropiarse de su espacio doméstico y transfigurarlo a su antojo, permite de alguna manera satisfacer sus necesidades y darles la opción, sin requerir una gran inversión, de cumplir sus deseos potenciales. Por otro lado, la liberación absoluta de servidumbres gracias al “soporte” central conlleva un cierto riesgo de cara a este desarrollo prospectivo. La ausencia de catalizadores o condensadores de esa futura reconfiguración podría ocasionar que, ante una libertad absoluta, los usuarios de la vivienda no fueran capaces de gestionar por su cuenta el espacio de forma óptima y acabasen empeorando las condiciones ambientales de las que disponen de salida. Sería interesante poder apreciar, en estas mismas plantas, de una serie de configuraciones alternativas al modelo requerido por los requisitos del programa en el concurso, que ilustrasen de manera didáctica y visual el potencial de desarrollo que este planteamiento puede ofrecer.

De cara a enfatizar la clara división entre “soporte” y “plementería”, las divisiones no estructurales entre distintos espacios se dibujan de manera arbitraría y desprejuiciada, mediante líneas quebradas, de directriz curva, en zigzag o construyendo nichos. Esta representación debería entenderse más como un manifiesto de intenciones, como un planteamiento teórico que mediante su materialización gráfica deja patente su verdadera vocación: la libertad de configuración.

Beside these non-bearing partitions sometimes appear structural supports with a very powerful presence in the interior space. Its rich and elegant materiality generates a notorious pulsation in a serialized space, giving so a strong identity to the rooms in which they appear. These stoned columns emphasize even more the freedom of non-structural partitions layout generating a curious contrast between wall and support, point and line that somehow reminds the use of these elements developed by Mies van der Rohe when he tried to point out the structural liberation of partitions. As Alejandro de la Sota would say in relation to walls executed in his work for the Civil Government of Tarragona, they are “partitions dancing in socks”.

Junto a estos tabiques liberados aparecen, en ocasiones unos soportes estructurales con una presencia muy potente en el espacio interior. Su materialidad rica y elegante genera una notoria pulsación en un espacio seriado, dotando así a las estancias en que aparecen de una fuerte identidad. Estos soportes de presencia pétrea enfatizan aún más la libertad de trazado de las particiones no estructurales generando un curioso contraste entre muro y soporte, punto y línea que recuerda de alguna manera al uso que de estos elementos desarrollaba Mies van der Rohe cuando pretendía, precisamente, poner en valor la liberación estructural de las particiones espaciales. Como diría Alejandro de la Sota en relación a la tabiquería ejecutada en su obra para el Gobierno Civil de Tarragona, son “tabiques bailando en calcetines”.

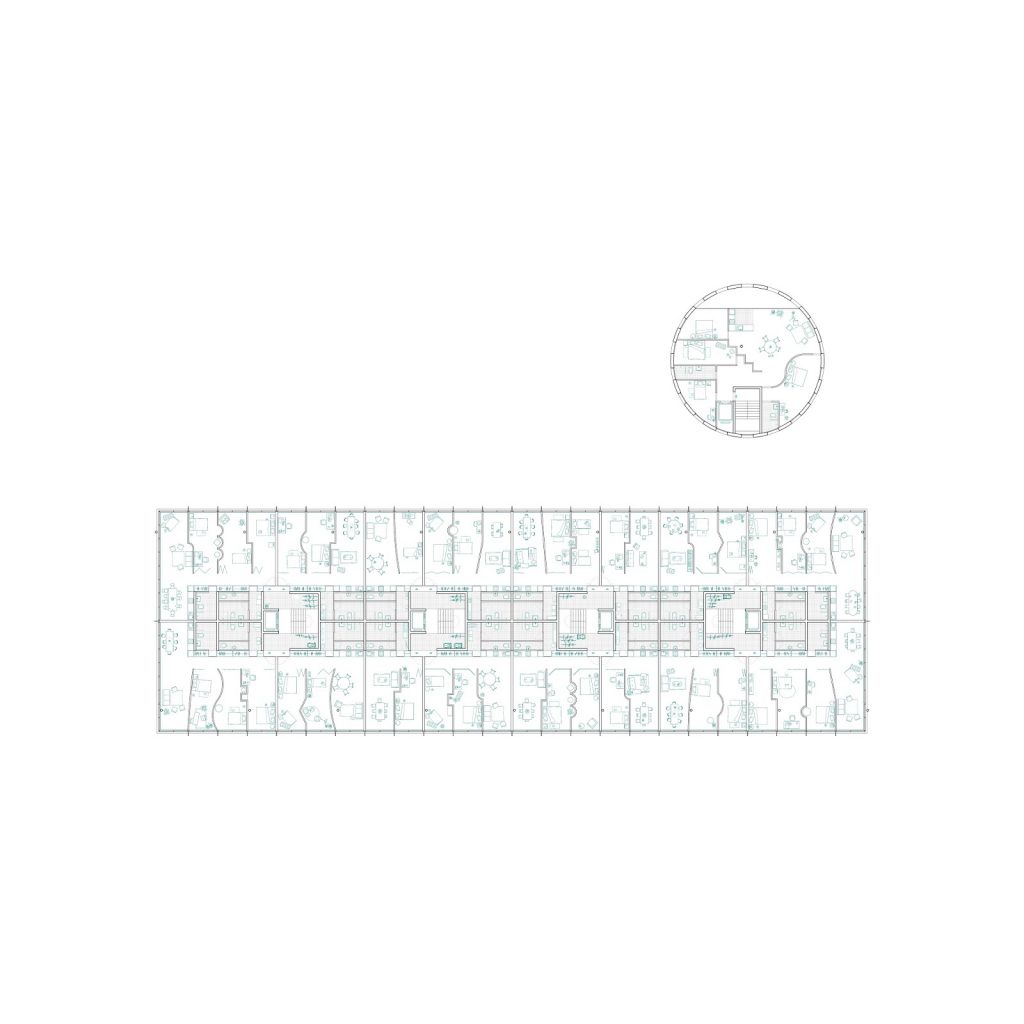

In models where the almost absolute freedom of spatial reconfiguration is primed, it is difficult to define privacy gradients considering specific spatial transitions based on a “support – movable units” scheme. Thus, the access to the private space from the public is made almost immediately, without any device preventing the supposedly privacy of dormitories from being occasionally disturbed by this situation.

These spatial transitions do appealingly in the cylindrical volume, where the possibility of deploying broader typologies, occupying the entire plant, allows to work on an idea of spatial polyvalence rather than that of absolute flexibility.

Here, the transition between public and private spaces is controlled and at the same time fluid through spaces of ambiguous size and use, with a major importance of the non-structural partitions of free layout. This spatial configuration does not reducet the possibility of reconfiguring and use the domestic space in almost infinite ways, intuitively imagined without difficulty from the drawn proposal. Rooms can change use and definition without affecting the correct configuration of the dwelling functional scheme, granting multiple ways of living that can be overlapped and alter over time, both at short intervals as night-day, as in longer ones, such as seasonal intervals.

Estas transiciones espaciales sí aparecen resultas de manera atractiva en el volumen cilíndrico, donde la posibilidad de desplegar tipologías más amplias, ocupando toda la planta, permiten trabajar sobre una idea de polivalencia espacial más que sobre la de flexibilidad absoluta.

Aquí, la transición entre espacios públicos y privados aparece controlada y a la vez fluida mediante espacios de dimensiones y uso ambiguos, con gran protagonismo una vez más de las particiones no estructurales de trazado libre. Esta configuración espacial no afecta para nada en la posibilidad de reconfigurar y utilizar el espacio doméstico de formas casi infinitas, que intuitivamente se dejan imaginar sin dificultad a partir de la propuesta dibujada. Las estancias pueden cambiar de uso y definición sin que ello afecte a la correcta configuración del esquema funcional del habitar, otorgando múltiples maneras de vivir que se pueden superponer y alterar a lo largo del tiempo, tanto en intervalos breves como noche-día, como en otros más largos, como podrían ser los intervalos estacionales.

En modelos en que se prima la libertad casi absoluta de reconfiguración espacial, considerando un esquema de “soporte – plementería” es difícil definir unos gradientes de privacidad en base a unas transiciones espaciales determinadas. Así, el acceso al espacio privado desde el público de comunicación se realiza de forma casi inmediata, sin que ningún dispositivo impida que el carácter supuestamente privado de los dormitorios se vea ocasionalmente perturbado por esta situación.

To conclude, we could establish that the project “Champs de Miràcles” is built on dualities. From the dichotomy equality-difference, present in all scales, from the urban to the domestic spatial definition, are derived those that give a special character to this proposal: flexibility-polyvalence and support-movable units. This set of opposites and at the same time complementary defines a model of collective housing that, faced with the homogenization imposed by excessively rigid programmatic requirements, gives the user part of the decision-making power over the spatial configuration of their habitat. Facing rigidity of box-like small spaces, the idea of living in a field of multiple possibilities.

A field of miracles.

Para concluir, podríamos establecer que el proyecto “Champs de Miràcles” se construye a partir de dualidades. De la dicotomía igualdad-diferencia, presente en todas las escalas, desde la urbana hasta la definición espacial doméstica, se derivan aquéllas que otorgan un carácter especial a esta propuesta: flexibilidad-polivalencia y soporte-plementeria. Este juego de contrarios y a la vez complementarios define un modelo de vivienda colectiva que, frente a la homogeneización impuesta por unos requisitos programáticos excesivamente rígidos, cede al usuario final parte del poder de decisión sobre la configuración espacial de su hábitat. Frente al modelo impuesto de caja, de pequeños espacios rígidos, la idea de habitar en un campo de múltiples posibilidades.

Un campo de milagros.

Every image by:

fala atelier