*** Article written by Nieves A. Calvo López ***

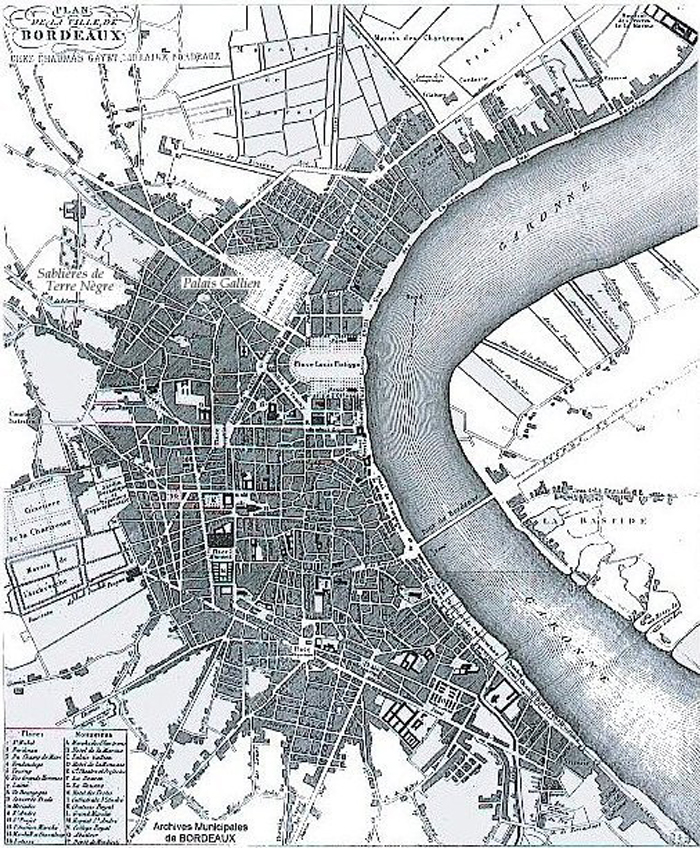

Europe. France. Bordeaux. Second World War. Summer of 1940. The country was invaded by the German army. With the defeat of France, the capability for German expansion across the Atlantic Ocean grew exponentially. (Image 1)

Europa. Francia. Bordeaux. Segunda Guerra Mundial. Verano de 1940. El país es invadido por el ejército alemán. Con esta maniobra, las posibilidades de expansión de Alemania hacia el Atlántico crecen de forma exponencial. (Imagen 1)

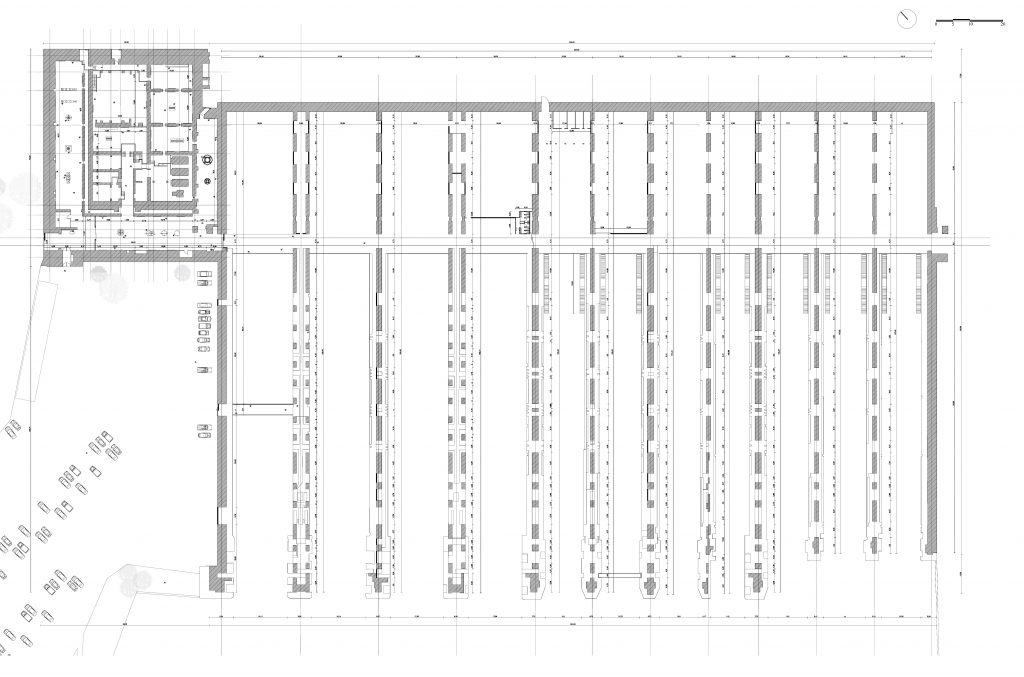

The situation in Bordeaux, one of the main European cities beside the Atlantic Ocean, was crucial for the German military. Founded around the third century B.C., the importance of the city as a commercial enclave was due to its harbors, which were created by the Romans. Its port structures do not access the sea directly; they are located about 50 km away, down the Garonne River, which is the axis of the city’s growth. When the Second World War broke out, the city of Bordeaux was the fourth most populated in France. Due to its proximity to the sea, the German army thought the city would be an essential point at which to build a base for their submarines. Ships would be well-protected from English attacks on their way to the Atlantic. Also, this route avoids the English Channel. (Image 2)

La situación de Burdeos, una de las principales ciudades europeas al borde del Atlántico, era crucial para los militares alemanes. Fundada en torno al siglo III a.C, la importancia de la ciudad como enclave comercial fue posible gracias a sus puertos, creados por los romanos. Sus estructuras portuarias no dan directamente al mar, que se sitúa a unos 50 km de distancia, sino al río Garona, eje de su crecimiento. Cuando estalló la Segunda Guerra Mundial, la ciudad de Bordeaux era la cuarta más poblada de Francia. Pese a no tener salida directa al océano, los alemanes pensaron que la ciudad sería un punto esencial donde construir una base para sus submarinos, que quedarían más protegidos de los ataques ingleses en su camino al Atlántico evitando además el canal de la Mancha. (Imagen 2)

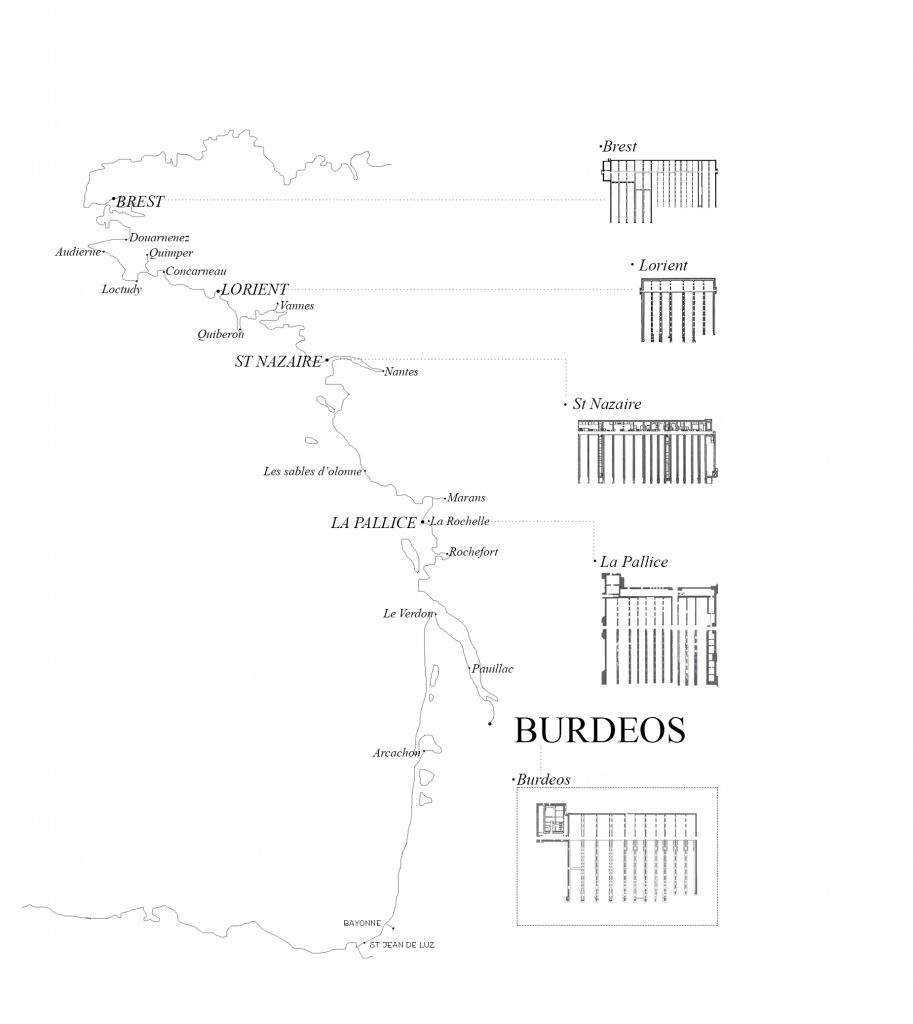

During the First World War, the submarines were grouped together without protection; they were at the mercy of the weather and enemy attack. However, during the Second World War, the risk of bombing the fleet required the creation of a series of submarine hangars, inside which the Germans could both maintain and shelter the ships. Since the beginning of the war, five bases were built along the Atlantic coast: Brest, Lorient, St-Nazaire, La Rochelle and Bordeaux. These cities were chosen because their represented strategic points that would allow the German army to advance quickly without resupplying from Germany. All of these former bases still preserve their huge concrete structures; they are a silent witness to what happened within their walls. (Image 3)

Durante la Primera Guerra Mundial, los submarinos se agrupaban sin ningún tipo de protección, a merced de las inclemencias meteorológicas y del ataque enemigo. Sin embargo, el peligro de bombardeo a las flotas propició que durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial se crearan una serie de hangares de submarinos donde poder resguardar y realizar labores de mantenimiento a los sumergibles. Desde el inicio de la Guerra, se construyeron cinco bases en torno a la costa Atlántica: Brest, Lorient, St-Nazaire, La Rochelle, y Bordeaux fueron las ciudades escogidas donde generar puntos estratégicos que permitirían a los alemanes avanzar más rápido sin desplazarse a Alemania. Todas ellas conservan todavía hoy en día estas enormes estructuras de hormigón, testigos mudos de lo que sucedía entre sus paredes. (Imagen 3)

The submarine base at Bordeaux was built between September 1941 and June 1943 and was completely abandoned in June of 1944, only two days after the last submarines left the harbor. Enclosed in its walls, the submarines of the German navy, also known as U-Boats, were repaired and protected. The reasons that Bordeaux was one of the five French military enclaves were wide-ranging: its harbor is one of the deepest in France and is located close to Royan, a city that has important port facilities. Furthermore, this city allowed the base to be built in the shortest time possible, since raw materials were obtained without difficulties due to their easy accessibility. For its construction, the German military took advantage of the cheap labor of the Spanish refugees in France, who abandoned their country after the civil war of the 1930s. As a reminder of the work of the Spanish prisoners who raised the bunker, a commemorative plaque decorated with the republican flag is located a few meters away from the building entrance. Another 2,500 people of other nationalities were also involved in the construction. (Image 4, 5,6)

La base Sous-Marine de Bordeaux, se construyó entre septiembre de 1941 y junio de 1943 y fue completamente abandonada en junio de 1944, tan sólo dos días después de que los dos últimos sumergibles salieran del puerto. Entre sus muros, se resguardaban y reparaban los submarinos del ejército alemán, también conocida como la U-Boat. Las razones de la elección de Burdeos como una de los cinco enclaves militares franceses fueron variadas: su puerto es uno de los más profundos de Francia y se situaba cerca de Royan, que cuenta con importantes instalaciones portuarias. Además, esta ciudad permitió que se construyera en el menor tiempo posible, con materias primas que se conseguían sin gran dificultad y buenas comunicaciones. Para su construcción, los alemanes aprovecharon la mano de obra barata que suponían los refugiados españoles en Francia, que habían abandonado el país tras la Guerra Civil de los años 30. Aunque participó gente de diversas nacionalidades (unas 2500 personas), una placa conmemorativa decorada con la bandera republicana se sitúa a pocos metros de la entrada de la base recordando el trabajo de los prisioneros españoles que levantaron el bunker. (Imagen 4,5,6)

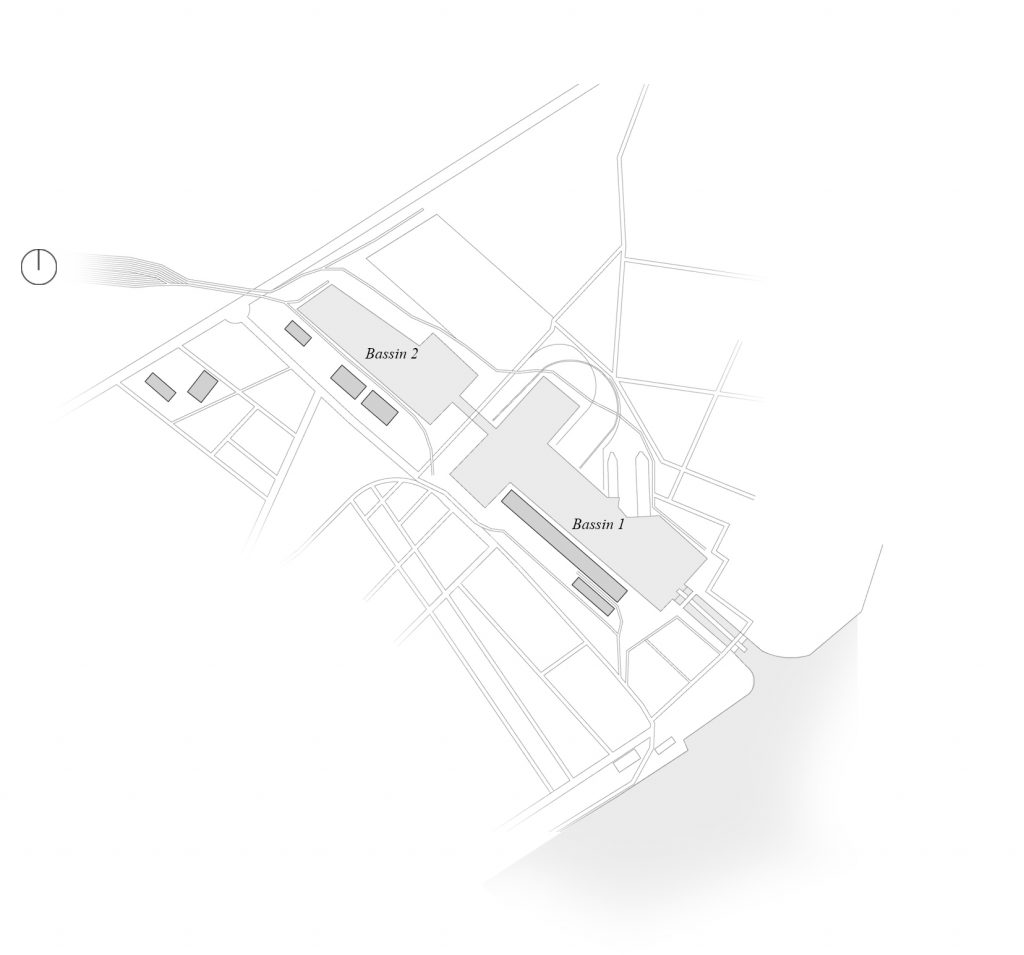

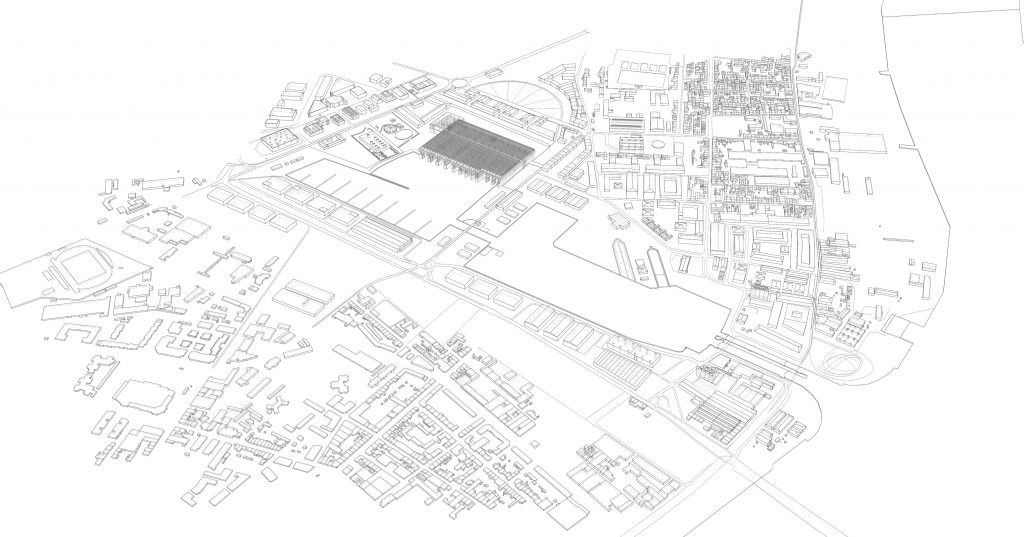

The urban consequences of the submarine base construction were numerous. Its realization was orchestrated by the Todt organization, the civilian and military engineering group of Nazi Germany, who were in charge of a large number of wartime projects. Before and during the Second World War, they built many buildings both in Germany and in other countries dominated by the Nazis. In the case of Bordeaux, they decided to build the base outside the historical center, in the industrial harbor of Bassin à Flot. The two locks of the port had to be reinforced with concrete in order to strengthen the infrastructure, and they were finished shortly before the German army abandoned the city. These structures were built as concrete “pools” or “bassins,” and their principal use is major water control. Prior to the base and the bassins´s creation, small buildings populated the surrounding areas, such as a railway line that was modified later to allow it to cross the interior of the huge hangar on its principal axis. After the construction of the bunker, the railway became less useful and progressively disappeared. Today, only a few traces remain still visible on the pavement. (Image 7 and 8)

Las consecuencias a nivel urbano de la construcción de la base submarina fueron numerosas. Su realización la llevó a cabo la organización Todt; el grupo de ingeniería civil y militar de la Alemania nazi y fueron los encargados de desarrollar una gran cantidad de proyectos de construcción tanto civiles como militares. Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial y previamente a la misma, construyeron numerosos edificios tanto en Alemania como en los países dominados por los nazis. En el caso de Burdeos, decidieron edificar la base fuera del centro histórico, en el puerto industrial de Bassin à Flot. Las dos esclusas de este puerto tuvieron que ser reforzadas con hormigón para mejorar la protección terminándose poco antes de que el ejército alemán abandonara la ciudad. Dichas estructuras se construyeron como “piscinas” hormigonadas o “bassins” cuya ventaja principal se basaba en un mayor control del agua. Previo a la creación de la base y de los bassins, pequeñas construcciones poblaban la zona, así como una línea de ferrocarril que se modificó posteriormente para que cruzara el interior del enorme hangar por su eje principal. Después de la construcción del bunker, los raíles fueron perdiendo utilidad hasta desaparecer por completo, quedando solo algunas trazas aún hoy apreciables en el pavimento. (Imagen 7 y 8)

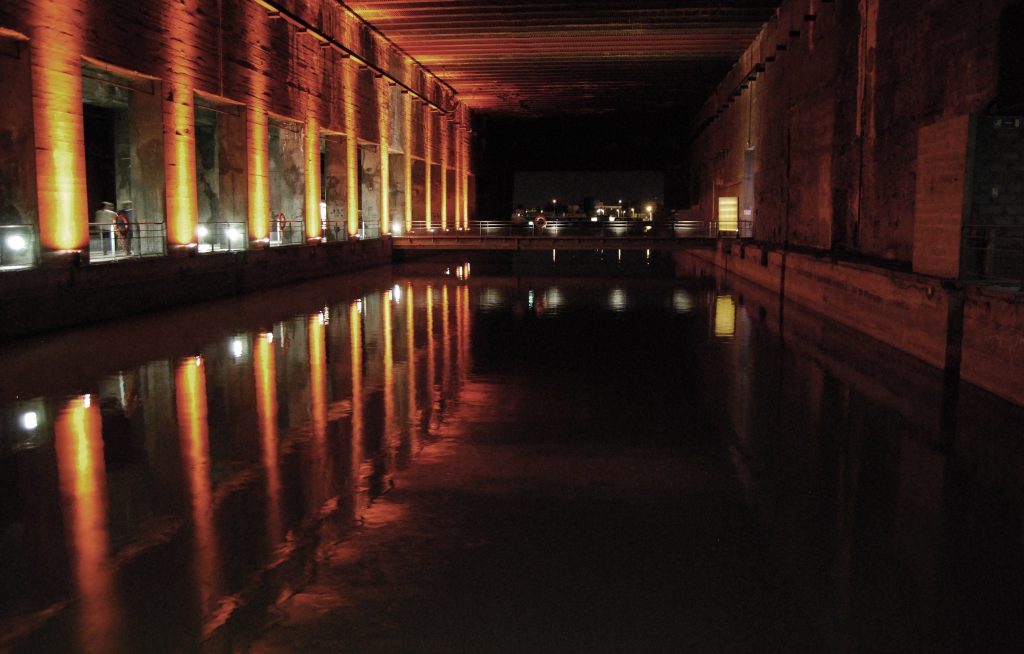

The enormous base, of around 42,000 square meters, consists of two buildings of different sizes entirely built of reinforced concrete. The main building has eleven alveolus, or water entrances, of similar dimensions which are aligned in parallel, joined by a perpendicular principal axis that crosses both constructions. Every alveolus has a water zone, where the submarines entered the building and surfaced, and a paver zone, where the machinery was located and also served as a material storage. In addition, the seven central alveolus could be used as a dry-dock if necessary. Of the two buildings that comprise the base, the principal is read as a huge porch covering the structures that, like fingers, penetrate the construction. There is no envelope. The air, cold and humidity flow over most of the base. Birds freely traverse the building. (Image 9, 10,11)

La enorme base, de unos cuarenta y dos mil metros cuadrados, se compone de un conjunto de dos edificios de diferente tamaño construidos enteramente en hormigón armado. El edificio principal, está formado por once alvéolos o entradas de agua de similares dimensiones y paralelos entre sí, que se unen mediante un eje principal perpendicular que atraviesa los dos cuerpos. Cada alveolo cuenta con una zona de agua, donde los submarinos entraban al edificio y salían a la superficie, y una zona pavimentada donde se situaba la maquinaria y que servía de almacén de material. Además, los siete alveolos centrales podían utilizarse como dique seco en caso de necesidad. De los dos cuerpos que componen la base, el principal se dispone como un gran porche cubriendo las estructuras que a modo de dedos penetran en el edificio. No hay cerramiento. El aire, el frío y la humedad circulan por prácticamente la totalidad de la base. Los pájaros atraviesan libremente el edificio. (Imagen 9,10,11)

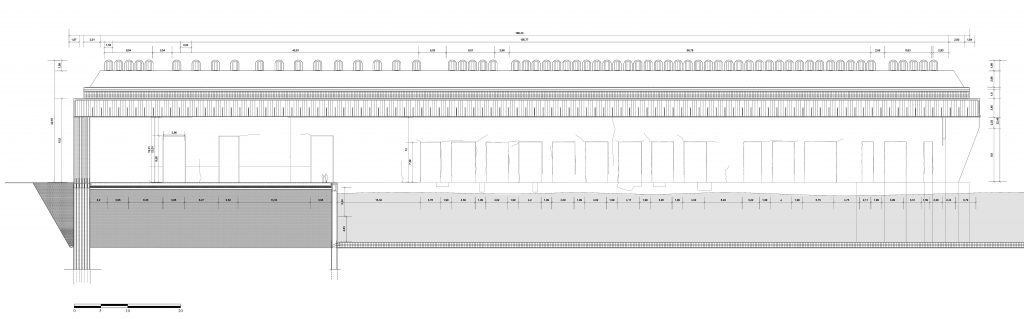

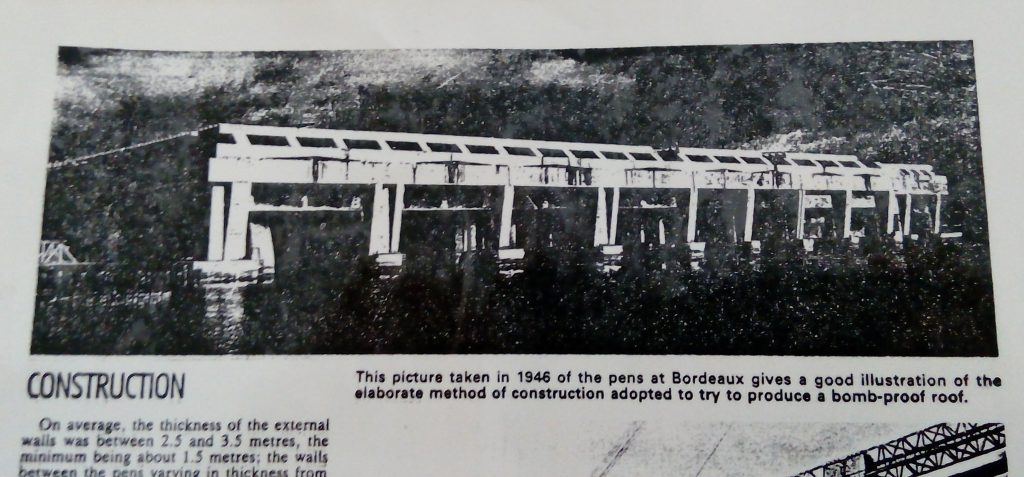

The mega-structure of brutalist concrete has huge panels, of almost two meters wide, which separate the alveolus and support the roof located twelve meters above. The load-bearing components intercalate spaces that associate the water entrances, creating an orthogonal visual game of connection and disconnection almost continuously. A metallic reddish plate is visible in the totality of the ceiling and was possibly used as a lost formwork for a concrete roof of five meters in thickness. This structure was possible due to the location of metallic trusses in parallel every one and a half meters. Above it, a series of concrete walls perpendicular to the roof’s structure support the transversal beams, or “fangrost,” which were specifically created to protect against bombing. (Image 12, 13, 14,15,16,17)

La mega estructura de hormigón brutalista se compone de enormes paneles de casi dos metros de espesor que separan los alvéolos sujetando una cubierta situada a doce metros de altitud. Los elementos portantes intercalan espacios de relación entre las entradas de agua, creando un juego ortogonal de conexión y desconexión casi continua. En la totalidad del techo es visible una chapa metálica en tonos rojizos que fue utilizada posiblemente como encofrado perdido de una cubierta de hormigón de cinco metros de espesor. Esta estructura fue posible gracias a la colocación de cerchas metálicas situadas en paralelo cada metro y medio. Sobre ella, se construyeron una serie de muretes de hormigón perpendiculares a la estructura de la cubierta, que sujetan las vigas transversales o “fangrost”, creadas específicamente para evitar bombardeos. (Imagen 12,13,14,15,16,17)

Interior image by Nieves Calvo. (2014)

Longitudinal section. Drawing by Nieves Calvo

Transversal section. Drawing by Nieves Calvo

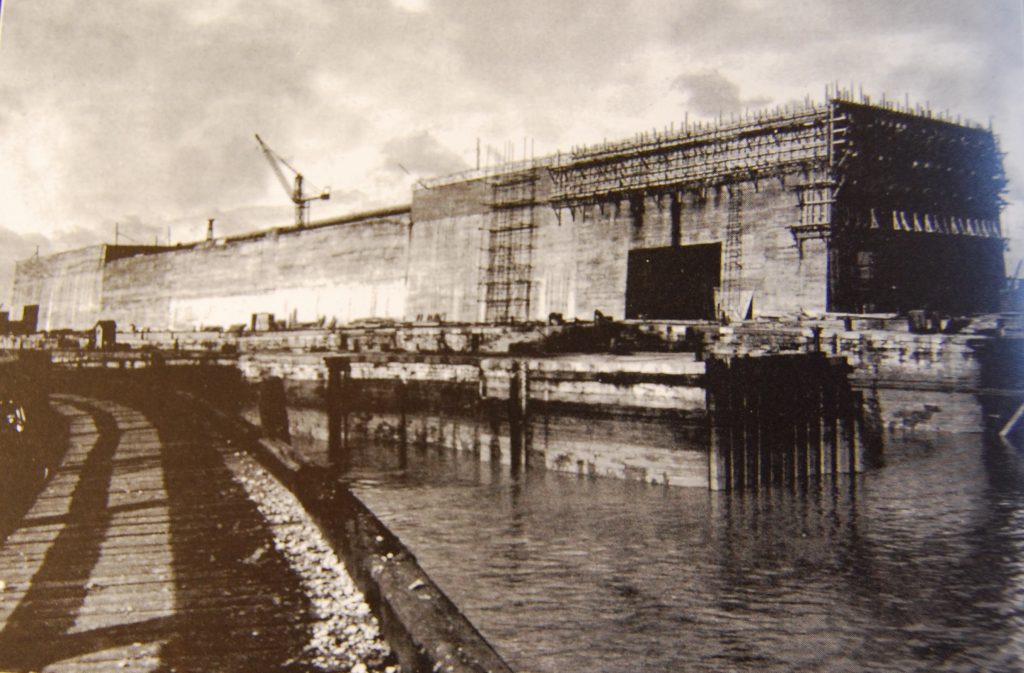

Construction of the submarine base. 1942

Newspapers images. 1943. From Jean Moulin private foundation, Bordeaux

Newspapers images. 1943. From Jean Moulin private foundation, Bordeaux

In addition to the water entrances, the building is a labyrinth of corridors, halls and several storage rooms. Some bunkers of small size were built around the base in order to safely keep ammunition, combustibles and explosives among others. (Image 18, 19)

Además de las entradas de agua, el edificio es un laberinto de pasillos, salas y diversos almacenes. Varios bunkers de menor tamaño se construyeron en torno a la base para poder guardar de forma segura municiones, combustible y explosivos, entre otros. (Imagen 18,19)

Sailing between the sea and the base was not easy: the French sailors were the only ones who could do it, and it was only possible to enter the building twice a day during the high tides. Also, in May of 1943 the American army tried to bomb the base, but, far from destroying the hangar, it was largely undamaged. The transversal beams of the roof were slightly damaged in the northwest zone, but it was not necessary to repair them.

La navegación entre el mar y la base no era sencilla: Los marinos franceses eran los únicos que podían realizarla y solo era posible acceder al edificio dos veces al día durante la marea alta. Además, en mayo de 1943 el ejército americano intentó bombardear el edificio, que lejos de destruirse, quedó prácticamente intacto. Las vigas transversales de cubierta, quedaron dañadas ligeramente en la zona noreste pero no fue necesario repararlas.

The submarine base was completely abandoned in 1944, only three years after the beginning of its construction. Practically indestructible, over time it was consolidated as a military ruin in an industrial zone of modest growth. During the 1980s a few alveolus were rehabilitated as a naval museum, but later the whole structure was again abandoned. Since its abandonment, the base has become a place of peregrination for the inhabitants of Bordeaux due to its spatial singularity. (Image 20)

El edificio fue completamente abandonado tan solo tres años después del comienzo de su construcción. Prácticamente indestructible, se consolidó como una ruina militar en una zona industrial de tímido crecimiento. Durante los años 80 se reutilizaron algunos alvéolos como museo naval pero de nuevo quedó abandonada. A pesar de ello, se afianzó desde su abandono como un lugar casi de peregrinación para los habitantes de la ciudad debido a la singularidad de su espacialidad. (Imagen 20)

Over the last few years, several regeneration projects of the Garonne riverside allowed the development of the center of Bordeaux, which was recently declared a UNESCO World Heritage site. This rehabilitation of the riverside has continued, spreading to Bassin à Flot, which has become an important cultural focus for the city.

Durante los últimos años, diversas obras de regeneración de la ribera del Garona han permitido que el centro de Burdeos haya evolucionado hasta ser declarado Patrimonio Mundial de la Unesco. Esta rehabilitación de las orillas del río ha ido en aumento durante los últimos años llegando hasta Bassin à Flot que se ha convertido en un potente foco cultural de la ciudad.

From the two buildings that form the base, only 12,000 square meters are used. They currently accommodate a cultural program mainly focused on temporary exhibitions, art spectacles and musical events, most of them at night. The remaining 30,000 square meters are closed to the public. The building is not accessible anymore from its principal axis, because the entrance is now located at one of the sides of the base. Visitors can now cross a bridge, which was lately added, that extends over the first alveolus. (Image 21)

De los dos edificios que componen la base, solo se utilizan doce mil metros cuadrados que en la actualidad cuentan con un programa cultural enfocado principalmente a exposiciones temporales, espectáculos de arte y eventos musicales, la mayor parte de ellos nocturnos. Los treinta mil metros cuadrados restantes permanecen cerrados al público. El edificio no es atravesable por su eje principal como lo fue antiguamente, pues se accede por uno de los laterales de la base atravesando un puente incorporado posteriormente y que cruza el primer alvéolo. (Imagen 21)

The construction of the submarine base reflected the spirit of the era in which it was built, when it was necessary to reinforce its position in the face of a determined enemy, using the best technological resources at their disposal. Its spatiality, besides being contemplated from the functionality for which it was created, tells us about reflection, feelings, shines, and textures that stimulate the senses in a humid environment of great architectural quality and enormous potential. (Image 22-32)

Su construcción reflejó el espíritu de una época que buscaba reforzar su posición ante el enemigo, utilizando para ello los mejores recursos tecnológicos a su alcance. Su espacialidad, aunque no contemplada desde la funcionalidad con la que fue creada, nos habla de reflejos, brillos, sensaciones y texturas que estimulan los sentidos en un entorno húmedo de gran calidad arquitectónica y enorme potencial. (Imagen 22-32)

Interior image by Nieves Calvo. (2014)

Interior image by Nieves Calvo. (2014)

Interior image by Nieves Calvo. (2014)

Exterior image by Nieves Calvo. (2014)

Exterior image by Nieves Calvo. (2014)

Exterior image by Nieves Calvo. (2014)

Lormier, Dominique, “La Base Sous-marine, 1940-1944” Questions de mèmoire, Bordeaux, Editions C.M.D

Lormier, Dominique, “La Base Sous-marine, 1940-1944” Questions de mèmoire, Bordeaux, Editions C.M.D

Lormier, Dominique, “La Base Sous-marine, 1940-1944” Questions de mèmoire, Bordeaux, Editions C.M.D

Nieves A. CalvoLópez (Madrid – New York, 1991)

Architecture, art, design, perception, atmosphere, research and exploration of absolutely everything. Currently living and working in Manhattan. Architect from Higher Technical School of Architecture of Alcalá (ETSAUAH) who has previously lived, studied and worked in Madrid and Bordeaux. Passionate about the phenomenology in architecture, was granted a research fellowship to study the relationship between our memory and architecture whose conclusions are still being developed. Great defender of the need for deep research into new ways of confronting the architectural profession, as well as rethinking the crucial role that animals should have in our society.